By Tony Mauro : The National Law Journal

Published: Sep 22, 2016

The intense debate over how transparent presidential nominees Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump should be about their health gives rise to another question: What about the health of Supreme Court justices?

After all, the average age of the justices is 69—right between Clinton, who is 68, and Trump, who is 70. And the most extensive medical information about a Supreme Court justice that has been made public pertains to Antonin Scalia—though it was revealed after he died in February.

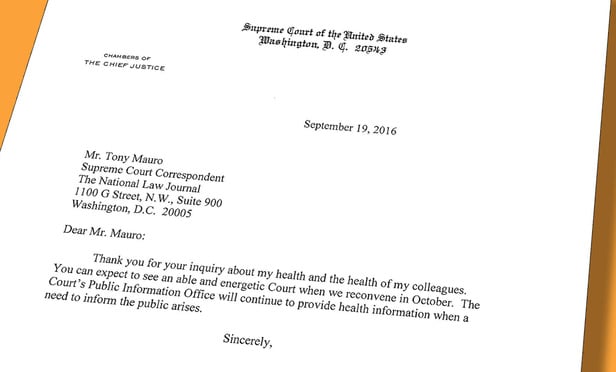

But the high court marches to its own tune. So when Law.com asked all eight current justices to make public their health statuses earlier this month, a single response came back from Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. this week. His answer, in effect, was: “Thanks for asking, but we’ll release information about our health when we feel the public needs to know.”

Here is the full text of the letter, sent by Roberts to Law.com on behalf of the entire court: “Thank you for your inquiry about my health and the health of my colleagues. You can expect to see an able and energetic Court when we reconvene in October. The Court’s Public Information Office will continue to provide health information when a need to inform the public arises.”

Roberts’ letter makes clear that the justices will continue to be the sole arbiters of what the public should be told about their health, limiting their disclosures to serious new ailments such as cancer or heart problems. Current and past justices have uneven policies about releasing such information, with most of them choosing to say nothing unless word leaks out.

The letter from Roberts was a classic response from a government institution that often lags behind others on issues of transparency. But transparency advocates and some court scholars argue that the justices, increasingly in the public eye and often viewed as political players, don’t deserve as much invisibility as they seem to want.

“The public does not need to be informed of every judicial medicine or ailment,” said Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, created two years ago to urge the Supreme Court to be more open. “But just as presidents and presidential candidates release basic information about their health from time to time, so, too, should the justices—much as each year they disclose details about their finances.” Health disclosures, Roth added, are important “so the public can have faith their top legal officials are operating at full capacity.”

‘MUCH WORSE THAN WE KNEW’

Concern over the lack of health information about the court predated the recent squabble between Clinton and Trump over their health disclosures. For some, Scalia’s death on Feb. 13 at a Texas hunting resort justified why justices should be more forthcoming.

It was not until after Scalia’s death that the public learned, through a letter from the attending physician of Congress that Scalia had “many chronic medical conditions,” including high blood pressure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea and coronary artery disease. Dr. Henry Monahan, whose office treated Scalia for 29 years, wrote the letter to the Texas judge who was assessing the cause of Scalia’s death, and the letter was made public only through a public records request under Texas law.

“Think about how much we learned about Scalia’s health after his death,” said court scholar David Garrow, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. “It was much worse than we knew.”

George Washington University Law School associate dean Alan Morrison, a longtime court-watcher, said that, if Scalia’s ailments had been publicly known before his death, the justice might have felt compelled to retire, resulting in a “more orderly succession.”

Northern Illinois University political scientist Artemus Ward, co-author of a book about how and why justices leave the bench, agreed. “Justices who know that their health will be disclosed to the public each year may step down before a negative report would be issued,” Ward said. “Those who favor term limits or mandatory retirement ages for judges would likely support such a disclosure requirement. It would likely lead to judges departing sooner rather than later.”

As it turned out, Scalia’s untimely death has disrupted the court’s functioning ever since, leaving it with an eight-member court while the Senate refuses to vote on a successor.

Just over a decade ago, the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist also sent the court reeling. He was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2004 but refused to retire as his health declined. “He was in 100 percent denial,” Garrow said.

Without revealing details about his health, Rehnquist believed he could survive for another year, according to Jeffrey Toobin in his 2007 book “The Nine.” Instead, Rehnquist died in office in September 2005 after Justice Sandra Day O’Connor had announced her own plans to retire. Current Chief Justice Roberts had been nominated to replace her but, after Rehnquist’s death, President George W. Bush hastily named him to the center chair. Bush then nominated Samuel Alito Jr. to replace O’Connor.

The U.S. Constitution provides no mechanism for the removal of impaired or disabled justices, other than impeachment. Fifty of the court’s 112 justices through history have died in office.

The increasing average age of the justices also poses the possibility, eventually, of mental as well as physical impairments.

Garrow is the author of an eye-opening 2000 law review article that detailed the “mental decrepitude” of Supreme Court justices through history—including, most recently, William O. Douglas and Thurgood Marshall. In many instances, Garrow wrote, justices who were losing their mental faculties refused to retire—and their colleagues were loath to nudge them toward the exit door. If the public learned anything at all about their conditions, it was usually too late.

LETTERS TO THE COURT

Against that backdrop, Law.com sent letters to all eight sitting justices on Sept. 6. Justices were asked to supply, by Sept. 20, as many details as possible about their current health conditions. “We are interested mainly in current and recent health issues—illnesses, conditions, surgeries and medications—that could, in the near- or long-term future, affect your professional work,” the letter stated.

The letters included two attachments: the detailed report on President Barack Obama’s latest physical exam in March 2016, typical of the regular disclosure presidents make about their health, and a 1987 New York Times article that reported on the health of then-sitting Supreme Court justices. That was apparently the last time a media organization sought health information about all the court’s members. Several justices responded to the newspaper in 1987 with varying degrees of detail.

All eight justices received the letters in early September, but court spokeswoman Kathy Arberg declined to say how it was decided that only Roberts would reply.

What did Roberts mean when he said the court would “continue to provide health information” when deemed appropriate? With the consent of the justices involved, the court has from time to time issued press releases about specific health issues—but never has it released periodic reports on their health in general.

A tally of the court’s website reveals six releases about justices’ health in the last 14 years. Four of the press releases pertained to the cancer and heart problems of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who has been the most forthcoming member of the court when it comes to health disclosures. Another release gave information about Rehnquist’s thyroid cancer surgery in 2004. The other discussed Roberts’ “benign idiopathic seizure” near his summer home in Maine in 2007, which had been reported by local news outlets.

Ginsburg has been open about her illnesses in part because retired O’Connor spoke movingly about her own 1988 breast cancer experience, according to Linda Hirshman, author of “Sisters in Law,” a book about the two justices. “Justice Ginsburg regards that as one of O’Connor’s most important accomplishments. She sees the value in telling people how they can live through these obstacles.”

Garrow and others think more routine disclosures are necessary. The increasingly high public profile of several justices and the court in general also makes public disclosure important, Garrow said. The court has become a significant target for advocates from all segments of the political spectrum.

As such, it is inevitable that the modern-day demand for maximum transparency about government institutions and leaders would expand to include the judicial branch. “It is such an opaque institution,” Garrow said. “It would be in the court’s own self-interest to be as transparent as possible about the justices’ health.”

Tony Mauro can be reached at tmauro@alm.com. On Twitter: @Tonymauro

Michael Paul Attorney at Law

Michael Paul Attorney at Law